Staring at a pair of feet next to my face, I tried to sleep. I put a sweater under my head because I loathed the stickiness of the sofa under my cheek.

The deck bar of the Bari-Durres ferry filled with a cheerful crowd, getting drinks and laughing loudly. It felt like they all knew each other and were happy to return home. Some started preparing a place to sleep on one of the round sofas.

I wanted to travel cheaply, so I didn’t book the cabin for the 10 hours ride. As a result, I had to share a couch in a deck bar with an elderly Albanian lady. Our sofa looked like a fort, surrounded by my panniers and her bags, including a bulky cool box.

Delayed by two hours, we entered the port in Durres when intense lightning cut the sky in half. The potholed streets turned into streams. Completely soaked, I arrived at my Airbnb on the outskirts and could finally recover after the exhausting boat ride. The rainy day gave me a perfect excuse to do nothing and prepare for the upcoming days filled with cycling and exploring.

If you’re looking for practical advice for cycling in Albania, check out my bike touring guide to Albania.

Durres

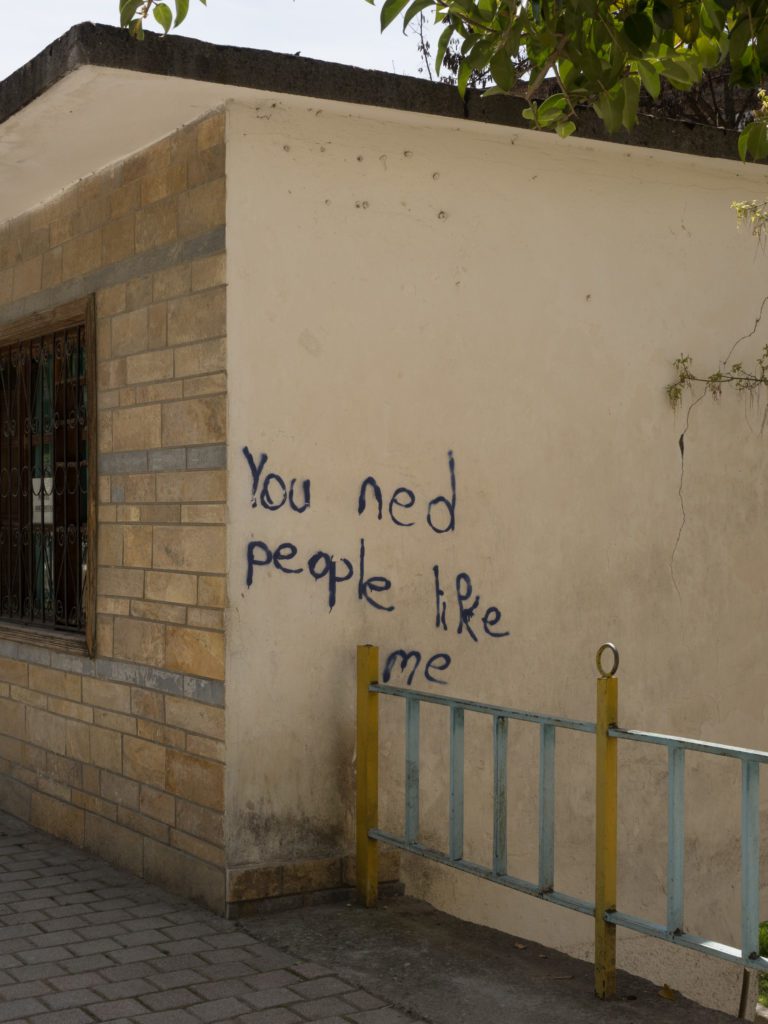

Durres was clearly not the award winner in the category Most charming city. Albania’s old capital and second-largest city was a holiday resort with plenty of restaurants by the sea, soulless apartment buildings and angular communist blocks.

In the middle of this concrete jungle, you could find an ancient Roman amphitheatre, discovered by pure chance in the 60s and a few columns that remained out of the Byzantine Market. I climbed one of the steep streets to look above the faded facades of socialist buildings and tangled electricity cables. White snow glistened on the mountains east of the city.

I left the city and headed south, following a surprisingly decent cycling lane, which was unfortunately too often treated as a parking space or pedestrian sidewalk. After a few kilometres of a busy road and an absolutely unattractive industrial area, I entered a different world.

Somewhere in the countryside

My bike jumped on numerous potholes in a dirt road crossing some villages. Chickens shifted from foot to foot in panic and clucked to warn their mates from a weird creature on two wheels.

The spring was already in full swing: the meadows were freakishly green, and the blossoming cherry trees added more colours to the landscape. The villages seemed vibrant. Elderly men in brown jackets rushed somewhere on their mopeds but always raised their hands to say hello.

In the vast fields, I could spot some bent backs of people working with scythes and sickles and donkeys loaded with cumbersome packs of straws. It was easy to romanticise this landscape, seeing it as a return to the past. There was a temptation to describe the people as hard-working but happy, but I couldn’t make a conclusion about their happiness just based on the smiles they cast me. I knew they’d been through a hell of a difficult life, with one of the most terrible regimes in the world. And 30 years after its fall, Albania was still facing poverty.

Caught up in observing the novel reality around me, I completely forgot to eat. I only realised that when pedalling became fatiguing, even on a flat road. Despite the low sugar levels, I made it to the nearest town. Small cafes were crowded with men slowly sipping their coffees or engaging in conversations. One of them noticed me looking around, moved his hand next to his mouth and simulated eating. He gave me a questioning look. I nodded, and he showed me a way to a bakery where I got 2 pieces of delicious burek with spinach.

After that, the straight road to Berat was just like a relaxing meditation. I set my focus on the snow-capped summits on the horizon and pedalled.

Berat

White Ottoman houses set in straight lines covered the hills on both banks of the Osum Rivers. Berat looked like a museum. I could clearly see why it was on the UNESCO list. Despite the historical character, the city was pulsing with life. On the Gorica bridge, a man was selling old tools. I crossed to the other side of the river and entered a narrow cobble-stoned street to my hostel.

I walked up the stone stairs feeling like entering a castle. The walls of this 17th-century house radiated the cold – air-conditioning was needless there.

– Where are you from? Poland? Poland is good – said Lorenc, the owner, when helping me carry the bike up the craggy stairs. His hair was grey, but his face looked fresh. Maybe it was his coy smile and warm glance that gave him the look of a youngster.

I shared the dorm with a 30-something American, let’s call him Ben, as I no longer remember his name. I don’t even feel guilty about it: he travelled around Albania for almost a year and referred to it as this country.

What places did you visit in this country? People in this country are hospitable. I don’t know how long I will stay in this country.

He only came to Albania because as an anti-vaxer he couldn’t go anywhere in Asia, where he was travelling before. He left the US 6 years earlier and had been travelling since, and as he said, the most important for him was to explore the culture. It wasn’t clear what he meant by that, as he mostly ranted about how corrupt the governments everywhere are and how travelling in India is difficult. But he loved it anyway, he said.

I don’t know why, but there is always one crazy person per trip I have to meet and have an absolutely ridiculous conversation with. Ben shared with me that he watched some YouTube videos of people who went to Ukraine during the war and stated that it’s not Russia but Ukraine who is bombarding the country. I politely told him that I had spent some time with refugees on the Polish-Ukrainian border, and their story was quite different.

– Yeah, maybe, but there is something about this war that the mainstream media is not telling us, I am sure. A bigger reason.

Luckily, I had a valid excuse to leave the hostel and get out of this conversation: I wanted to see The City of Thousand Windows, as Berat is called. It looked mesmerising in the last rays of the sun. The castle overlooked the river and the old houses on both banks. One by one, the muezzins from all the mosques were starting the call to prayer.

Berat’s mosques are stunning monuments of the Muslim faith and survived the years of repression from the side of the anti-religious communist regime of Enver Hoxha. However, one of them, Bachelor’s mosque has to deal with the disgrace of having a store with women’s underwear on its patio.

On the Boulevard Republika, people were enjoying the xhiro – as Albanians call the evening stroll. Everybody looked relaxed, enjoying the sunset, talking to friends, and getting a coffee in one of the outdoor cafes.

Pancakes with fresh apples and a small cup of thick Turkish coffee had fueled me before a long way along the Osum river. The road was rising gradually. In the valley, the vineyards formed a green chessboard. Still undiscovered by the mass audience, the region of Berat is producing world-class wines praised by connoisseurs that somehow make it to this forgotten corner of Europe.

-Where are you from? Where are you going? – A teenage boy on a bike showed up next to me somewhere around the town of Polican. – Why are you travelling alone? Don’t you have friends?

Osum Canyon

The walls on the sides of the milky blue river grew bigger. I entered the largest canyon in Albania – The Osum Canyon. Small waterfalls flowed spreading the refreshing aroma of ice-cold water.

Not sure how easily I would find a place to camp, I started looking around a good while before the sunset. Excited about spending a night close to this marvel of nature, I was still a bit cautious since it was the first night of wild camping in a new country.

There was a big off-road truck parked on a big flat meadow. I noted that if I couldn’t find anything better, I would go back there and ask those overlanders if I could pitch my tent next to them.

There was a dreamy spot by a little bay a few kilometres further but some workers were walking around a little wooden building there, so it didn’t meet my standards for a private campsite. After a good hour of search, I found a field between dense thorny bushes with some litter left by previous campers, including a single shoe and a few beer cans.

I refreshed myself in a small stream and started boiling the water. Instant noodles were the only thing I could force myself to cook after this long day.

From the hill on the other side of the road, I heard goat bells and the shouting of the shepherd. After the sun hid behind the summits, there only sounds were the chirping of birds and the trickling of the stream. A sound of an engine interrupted this idyll and suddenly stopped. I heard manly voices. The muscles on my back got tense, and I tried to withhold any movement and not make any sound. Am I not visible from the road for sure? Finally, the engine started again, and they left. I could relax. Their conversation lasted maybe a minute, but it felt like ages.

When I woke up in the morning, the humidity bit into my bones. I got out of the tent and walked down the stone steps closer to the river. I didn’t feel like moving, so I sat there with my coffee mug and watched the cloud of mist floating above the canyon. Once the sun finally has emerged from behind the mountain, I put my tent so that the wet sides face the sun.

It was getting hot again. I had almost no water left, and the stream didn’t seem like a 100 % safe option, as there were sheep on the hill on the other side of the road. I filled the bottles anyway, as I didn’t know if there was be something better before the next village, which was a long way up. I had a filter, but soon I found out that it was clogged. No water could run through it. It was useless.

After a few kilometres on a rocky and sun-exposed road, dehydration gave me headaches. I took a risk and drank some of the water without a filter. Luckily, all went fine, and I didn’t end up in the middle of the mountains with diarrhoea.

Prishte-Ballaban

In the village of Prishte, a guy in a white baseball cap with a German flag stopped me:

– You go to Ballaban? The road is very bad! You get coffee, cinque minutes stop, mangiare and super super.

He pointed at a small house on the side of the road. Cows and chickens were looking for something to chew on between the rumbling fences. Surprisingly many people lived in this skimpy house. Miro and his wife, their two daughters, grandparents, and a few other people somehow related to them.

I accepted the invitation. I knew a break would do me good.

Miro made coffee on a small gas stove and poured me a shot of raki.

– Local – he said with pride. – Tourists from Germany and France, buy it. Little money.

It was surprisingly good, with quite a mild taste, and unlike most rakis I had before, it didn’t burn my throat completely.

He massaged the area around his heart and said:

– Better than medicine. No korona when raki.

They asked me if I was hungry. Not wanting to cause my hosts too much work, I politely said no, but Miro refused to take it for an answer.

– Little, only a little.

His wife brought two pieces of byrek with spinach. The greasy and salty pastry was delicious.

– Local. Not from the supermarket – He said. – Only natural.

They started debating if I should continue on the route through the mountains. They didn’t think it was a good idea.

– Catastrophe – said Miro. – Pooch, pooch, very bad, very bad. What if the night falls? No one and nothing there.

They tried to convince me to go back to Berat and even offered I could stay with them.

I told them I would try, and if the road turned out very bad, I would turn back and camp in their yard. I promised to send the daughter a message on Instagram so that they knew I survived.

Quite soon, I encountered the first obstacle. The road became extremely soggy. There was no way to go around the mud and water.

I tried to find the driest path. Pooch, pooch – my shoes got sucked by the mud, and I finally knew what Miro meant by making this sound when describing the road to me. My rear wheel almost got stuck. I gave a big push and managed to get it out.

Behind the next swing, a white Suzuki was stranded in a big puddle. A German couple misunderstood the warnings the locals gave them and ignored the signs saying this road was only for 4×4. I asked if they were ok. Help was coming, they said, so I circled around the car and the mud and moved forward.

The road didn’t seem so bad. Or maybe I was just mentally prepared, after all the warnings and catastrophising I’ve heard. I anticipated much worse things, like carrying the bike over rock blocks. Sure, the mud and the steep road made my life difficult, but it was bearable.

Of course, cycling wasn’t even an option. It was hike-a-bike all the way up. But I felt strong and calm, not even in doubt if I could make it to Permet.

The views were stunning. The mountain peaks were still covered with snow. I was trying to imagine what was the view from them. Miro told me you could see it all the way to Italy if you climb these peaks.

The last stretch before the summit was steep. I could barely push my bike. Once the ground flattened, I felt euphoric.

Sheep were flocking on the shore of an emerald lake, and the panorama was raw and pristine. It was one of the most amazing landscapes I have ever seen. And I was completely alone there, except for the sheep and an eagle soaring through the sky. His course was balanced and stable, untouched by the gusts of wind.

The descent was rocky and steep, so I didn’t even dare to cycle on the first metres.

Scabrous sandstones made the landscape seem rugged and unwelcoming. Particles of hot dust were irritating my nostrils. I felt like on Mars or another planet.

I made it to the village of Pavar where I refilled my water bottles at a tap with colourful paintings. An older man came to me, alarmed by the barking of his dogs.

He asked if I came from the canyon, and when I said yes, he raised his eyebrows. I showed him my muddy legs, and he laughed, shaking his hand in disbelief that I was crazy enough to go through that road.

The descent to Ballaban was steep. I had to stop once because a dog was chasing me, running down the terraces of the vineyard. I stopped and started talking to him, and he just stayed where he was and let me slowly walk away.

I made it to the main road and was surprised by how empty and smooth it was. The valley was wide and surrounded by majestic mountains. Leaving the sun behind me, I enjoyed pedalling on the flats and finally being able to go faster.

Permet

I passed the town of Permet, got some snacks from the shop and headed to a campsite. Initially, I planned to wild camp, but I found a small campsite with great reviews on iOverlander. Everybody was enthusiastic about how great the owners were, and I couldn’t resist meeting them. The promise of a warm shower was tempting too.

-Hello, I am Donna, welcome to our campsite! An energetic woman in a beautiful hut rushed to show me everything, manoeuvring between chickens and dogs.

-What happened? You need to disinfect it – Donna pointed at my legs.

I looked down and noticed all the bruises and scars on my calves and thighs.

Donna shook her head when I told her where I came from.

– I was just telling these other guests that they cannot go that road, it’s terrible. Even my husband, an experienced offroad driver who knows the area very well, is exhausted when he comes from that road.

I pitched my tent next to a small caravan and took a deep breath looking at the mountains. A big furry dog rubbed against my leg. I knew it would be one of the places on the road that felt like home.

Pingback: Cycling Albania - practical bike touring guide - Wobbly Ride

Pingback: Cycling in Albania, part 2: Vjosa, the desolate Pindus mountains and Korce - Wobbly Ride

I just stumbled on your blog – looking for where to go north of Berat. Just today I did the same route from Permet to Berat today – what an adventure! And I even had stayed with Donna!