One name repeatedly came up in my conversations with other travellers and locals about Albania. Having heard about the bizarre city planning, unconventional architecture and magical aura, I had to visit Gjirokaster – a town which gave Albania the most atrocious dictator Enver Hoxha and the influential writer Ismail Kadare.

It was a strange city and seemed to have been cast up in the valley on winter’s night like some prehistoric creature that was now clawing his way up the mountainside.

Ismail Kadare, Chronicle in Stone

To describe Gjirokaster without overusing the words steep and stone is unattainable. The guys who started a town there must have had a boundless imagination. Why build houses on the flats in the valley if you can use the arduous slopes of Mount Sopot?

It was a slanted city, set at a sharper angle than perhaps any other city on earth, and it defied the laws of architecture and city planning. (…) it was surely the only place in the world where if you slipped and fell in the street, you might well land on the roof of a house – a peculiarity known most intimately to drunks.

Ismail Kadare, Chronicle in Stone

The city of stone

I pushed my bike up the cobbled street, opposing the gravity. A giant watermelon I placed on my luggage rack didn’t help. For the last few days, I passed dozens of stands with juicy fruits and the fields where they grew and only waited for the moment when I would stay in one place for a bit longer. Finally, the time has come. As soon as I saw watermelons in front of a small shop in the lower parts of Gjirokaster, I purchased one.

I booked a room in a small guesthouse. Esmeralda and Ronald welcomed me warmly. Their house was two centuries-old, and the family had owned it for generations. Before I even cooled down, Esmeralda served homemade warm halva and a strong coffee. As per Albanian custom, Ronald completed it with a shot of raki.

– Made from our grapes – he said with pride.

I received a room with wooden floors and wooden ceilings. From the window, I could see the beautiful shape of the fortress.

I took a quick shower and went to the bazaar. Everywhere around, I smelled a sweet but fresh scent of mountain herbs people tried to sell. An old woman dressed all in black carried a bulky linen sack on her back. Her small feet tucked into black leather shoes were carefully choosing the cobbles to step on: the red ones were more slippery, so it was safer to step on the black ones.

Gjirokaster bazaar

The bazaar was busy. After Gjirokaster appeared in the Dutch TV show Wie is de Moe?, many tourists from the Netherlands stormed here. Gjirokastra was slowly becoming more known to the mass audience, which definitely influenced what you can find on the stands in the bazaar. Meticulously crafted woodwork and stonework shared shelves with tacky bracelets, China-made magnets and souvenirs with Enver Hoxha (for those who like their morning coffee in mugs with cruel dictators).

I was getting hungry, so I went to grab some food in a fast food place with a Pepsi bar. The owner served me some pastry with cheese and grabbed a chair next to me to relish a cigarette.

She introduced herself as Lotilda. Living her whole life in Gjirokastra, she felt claustrophobic. All that she wanted was new experiences and a change of scenery.

-I want to go to Ireland, see and experience something new. I am tired of seeing the same things every day.

She stretched her arm and drew a line pointing at the bazaar. Shiny costumes, bright carpets, and charming cobbled streets didn’t impress her anymore.

The stone walls of the old mosque flashed in the warm evening light. The building was lucky – twelve out of thirteen mosques in Gjirokaster were demolished by the communists, who declared Albania an atheist state. Surprisingly, they saved the 18th-century bazaar mosque as a cultural heritage. During Hoxha’s regime, the circus used the temple as a training hall, since the high ceilings were perfect for trapeze acrobats.

Crafts in Gjirokaster

Strolling around the bazaar, I watched the craftsmen at work. Some were deeply immersed in their art, meticulously carving in wood or stone, while others observed the surroundings and chatted up anyone passing by.

As soon as I peeked at the lavish costumes in the small Atelier Lizeta, the craftsman wanted to teach me more about the Gijrokastran crafts. He didn’t speak English (or any other language I knew), and I didn’t know Albanian, but it wasn’t an obstacle for him. He called his son, a school boy, who translated every sentence over the phone.

The costumes were shamelessly luxurious, looking as if someone decided to keep all their money on their clothes. There was even a saying that people from this region would prefer to weave their gold into their clothes than save money.

The owner handed me a skirt. My arm sagged as the weight was heavier than I expected.

-It’s made of 80 elements – he said.

Everything in the atelier was hand-made, and the details were very time-consuming.

-This Lord Byron costume took months to finish – the owner of the atelier proudly presented a purple-golden blouse.

The English romantic was a great fan of Gjirokastran costumes. As today’s western Youtubers and bloggers who, in their reports, devote a lot of space to remarks about how cheap everything is.

–I have some very ’Magnifique’ Albanian dresses, the only expensive articles in this country. They cost 50 guineas each and have so much gold they would cost in England two hundred. – he wrote to his mum.

Cold war tunnel

There are two places in Gjirokaster where you can find relief from the heat: one is underground, and another is on the top of the hill.

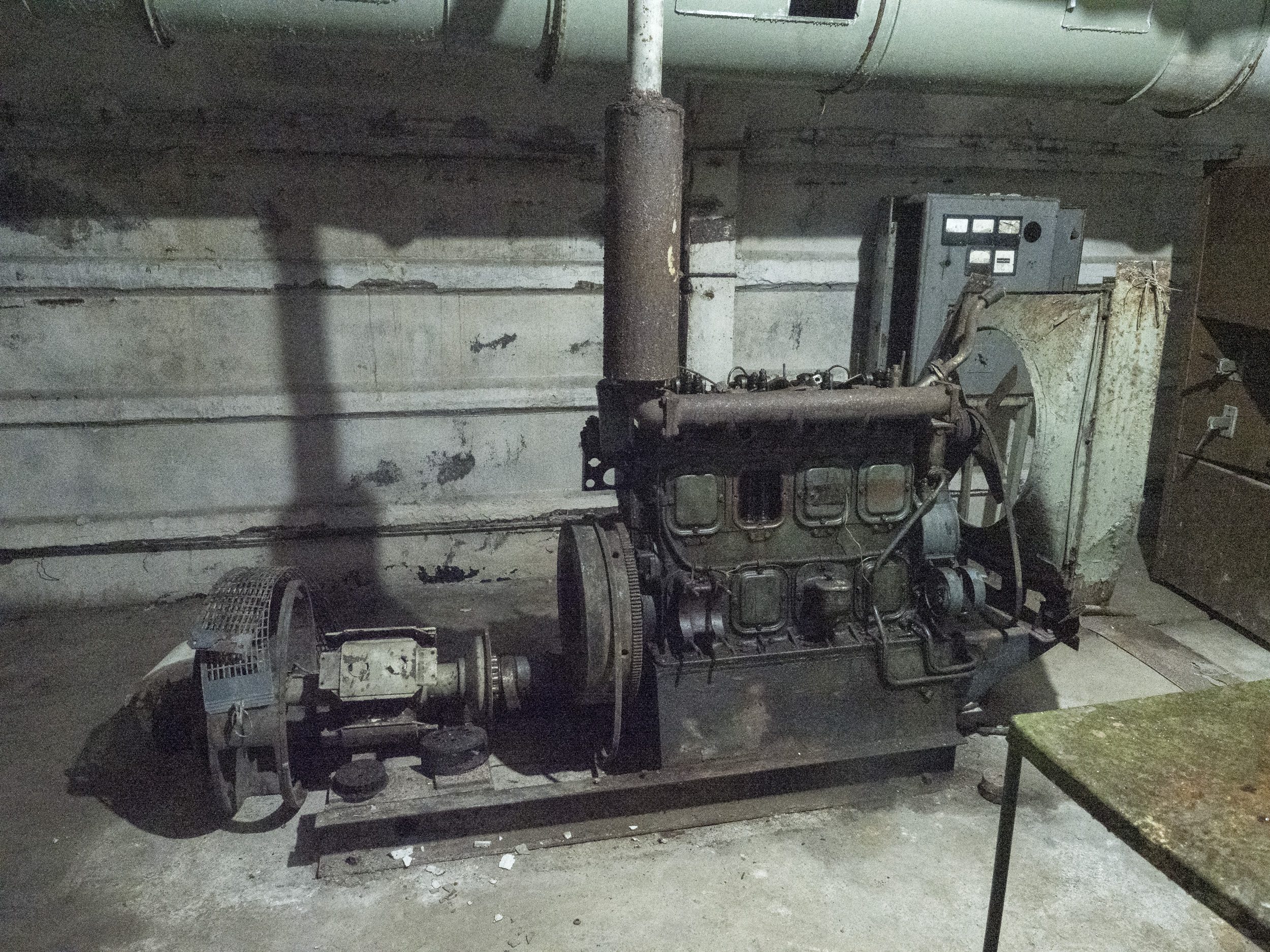

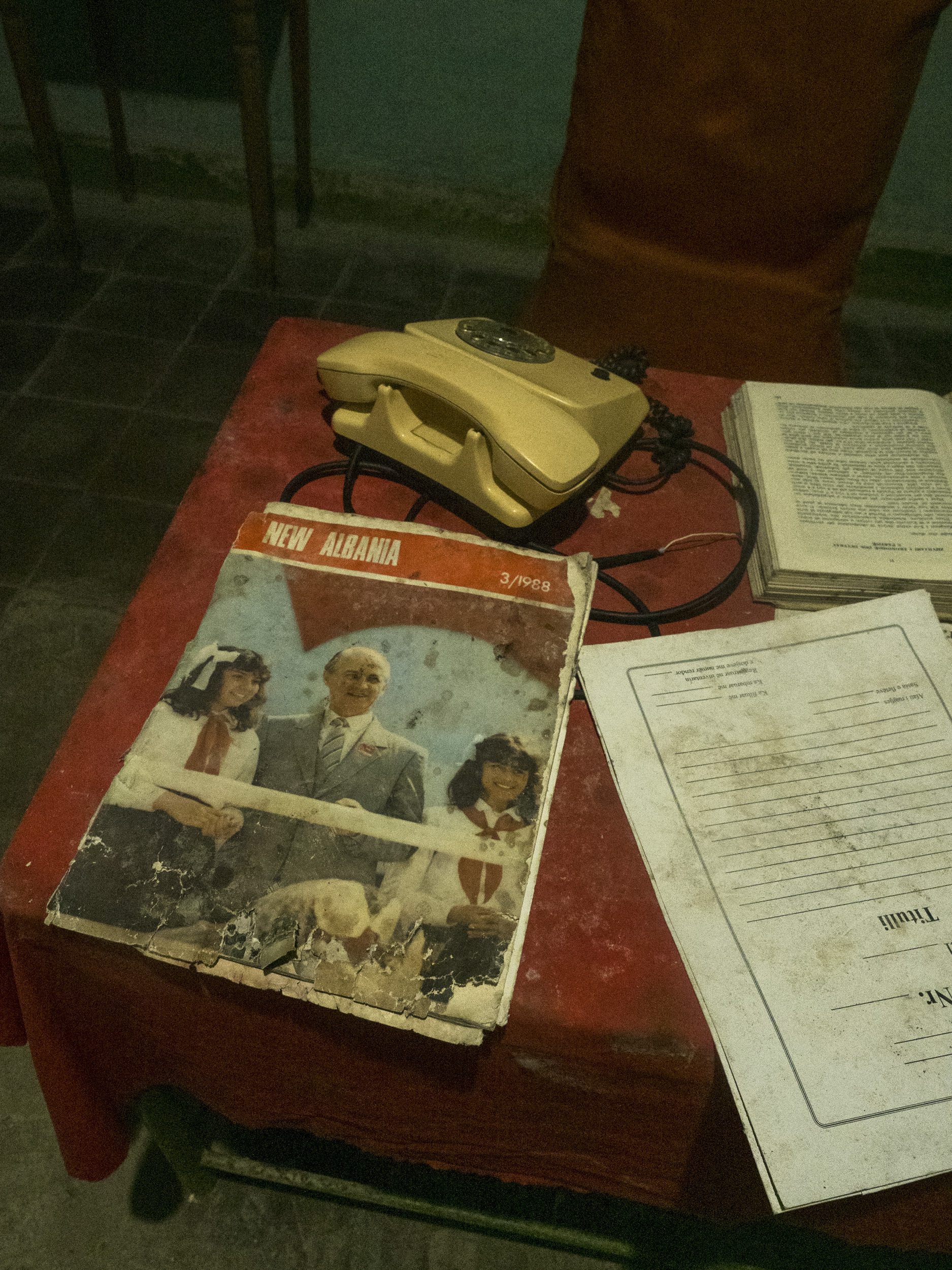

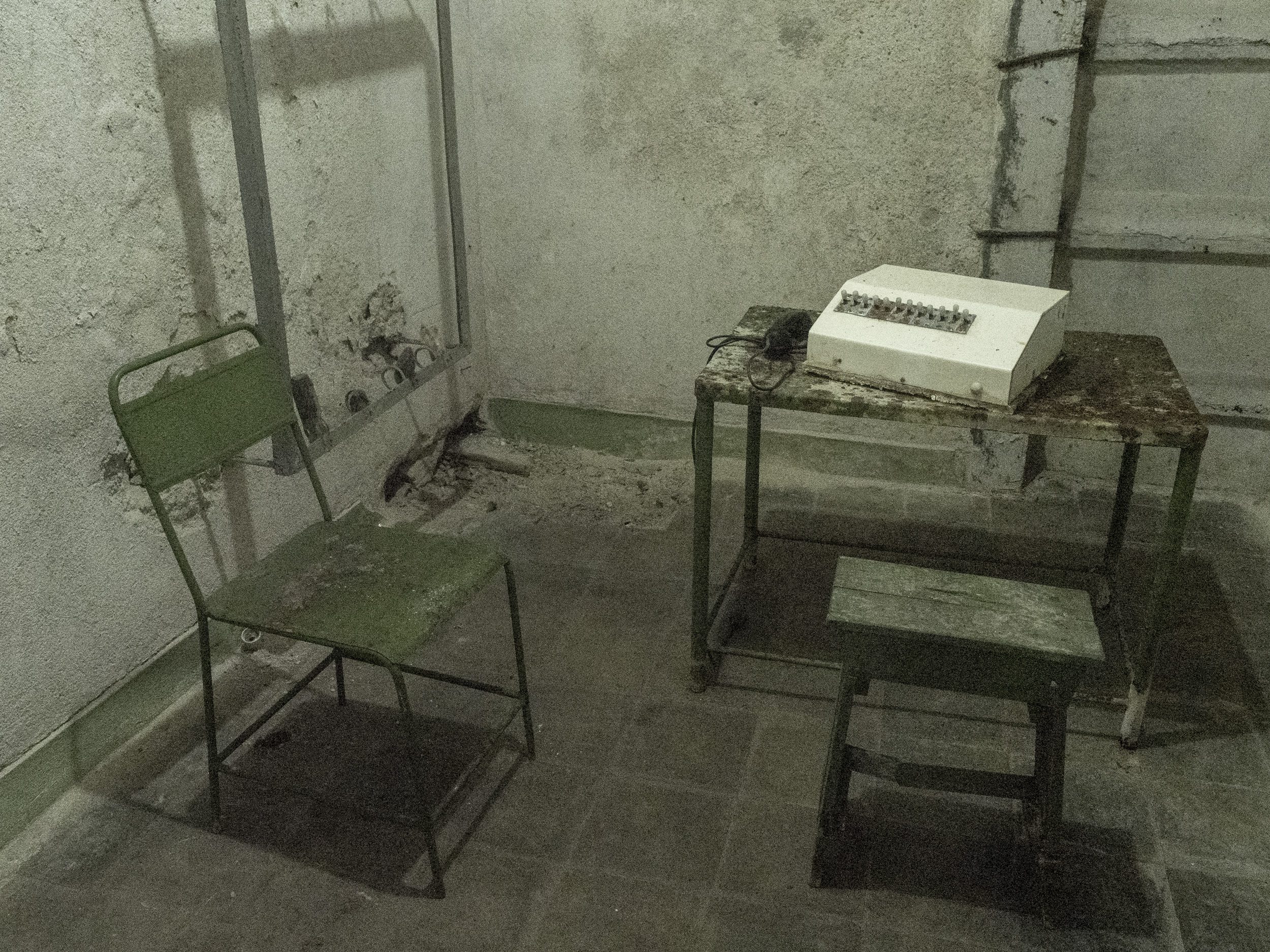

Under the city was a 700 metres long tunnel constructed in the 1970s. Kept secret for years, it was supposed to be a shelter for the most important officials and party members in case of a nuclear attack.

The attack never happened, like most threats Hoxha was paranoid about. The massive bunker under Gjirokastra was never used for anything else but storing documents. Most of the equipment was looted in 1997 when the country plunged into chaos after the collapse of Pyramid Schemes.

Pyramid Schemes and Albanian Civil War (1997)

During communism, the state had total control over the economy. Privately owned enterprises were strictly prohibited. You couldn’t even own sheep or goats because the party would confiscate them.

In 1992, after the fall of the communist regime, Albania had to adjust to the new open-market economy. Companies started to pop up like mushrooms. Enticed by the premise of financial wealth, Albanians began to invest. Everyone was suddenly free to enrich themselves, and some wanted to do it as fast as possible. Many companies were just get-rich-quick pyramid schemes offering no product or service, making returns only if new people invested. Some belonged to former State Security agents. Corruption was widespread, and the civil servants gladly accepted bribes from business owners.

Eventually, the pyramid schemes started collapsing one after another. Together, Albanians lost 1,2 billion USD. It led to protests, which turned into violence, and 2000 people died. Many robberies from the State Treasury and the weapon depots in the south of Albania happened during this time.

The Gjirokaster Castle

Before I found shelter from the heat in the castle, I had to sweat heavily on my way there. It was almost 40 degrees, and the short climb to the top of the hill felt like strenuous exercise.

In the little shade from the trees growing by the alley leading to the fortress elderly women were selling embroidery and jam.

-I was working all night to finish this jam – said one of them. Hysne was her name and her English was far better than I expected from a woman in her 80s, who has spent most of her life in a locked country and had never gone abroad.

-I just had to learn it. I need to make money somehow – she said.

The willingness to learn languages was an impressive quality of many people in Gjirokaster. Almost every time I went to a restaurant, a waiter would ask me where I was from and instantly start translating the positions on the menu into Polish.

Hysne’s lace drapes were beautiful, but I couldn’t buy souvenirs just yet, knowing I still had over a thousand mountainous kilometres on my bicycle ahead. She seemed angry as if she wasted her time talking to me and didn’t make any money on it.

The dark walls of the castle hid cannons abandoned by the Germans and Italians and a Fiat L6/40 tank. The tiny Italian vehicle looked rather cute than intimidating, but it was the only tank during World War II that could climb the precipitous streets of Gjirokaster.

Although the citadel has overlooked the town since the 12th century, most of the building we can admire today comes from the 18th century. It was built by Ali Pasha of Ioannina, a.k.a. The Lion of Ioannina.

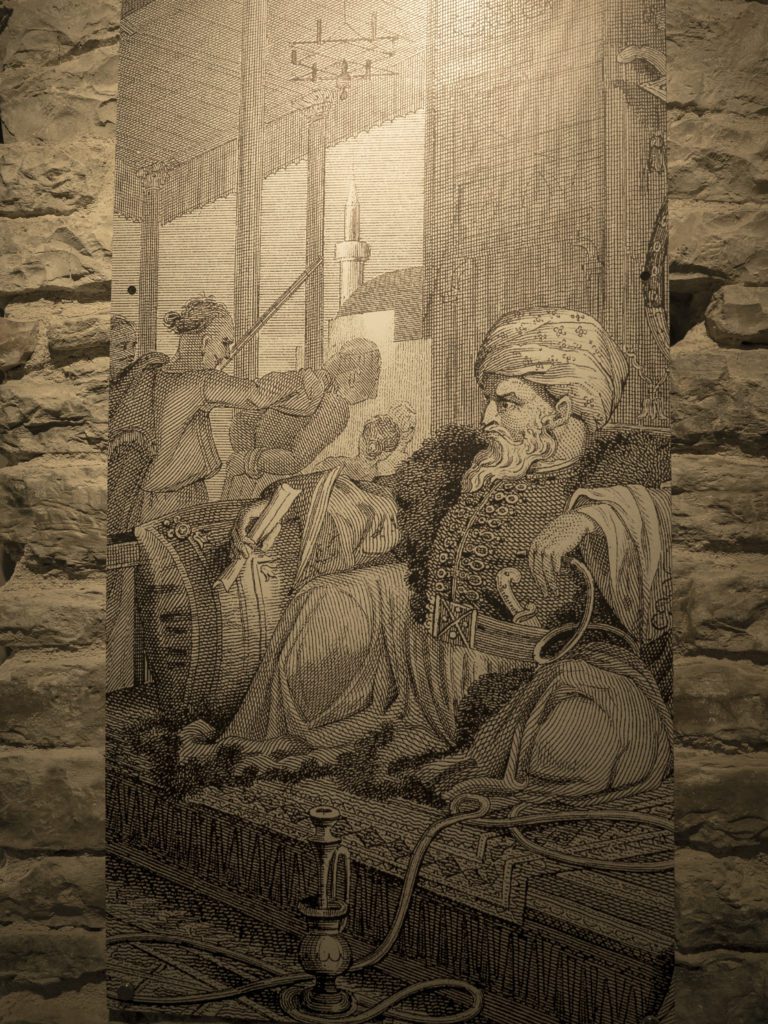

Who was Ali Pasha of Ioannina?

This Ottoman big fish was Albanian, born in the town of Tepelene, just 30 kilometres from Gjirokaster. As a youngster, he was just a bandit, looting and collecting wealth. He started with being a “master” for a group from his neighbourhood (among them the boys from Lazarat, during the Ottoman era known as a village full of good patriots and fighters and at the beginning of the 21st century as the cannabis capital of Albania). Thanks to his diplomatic skills and progressive approach, he gained influence. He networked with Pashas in the regions, helping them put down rebellions. Being opportunistic and allying with whoever offered him what he needed, he became a Pasha and a ruler of a nearly independent state of Ioannina.

He was an effective and powerful ruler who could gather an army of 50 000 men in just two or three days. He was also a cold-blooded despot. Lord Byron, hosted by Ali Pasha during his travels, called him a “remorseless tyrant guilty of the most horrible cruelties”.

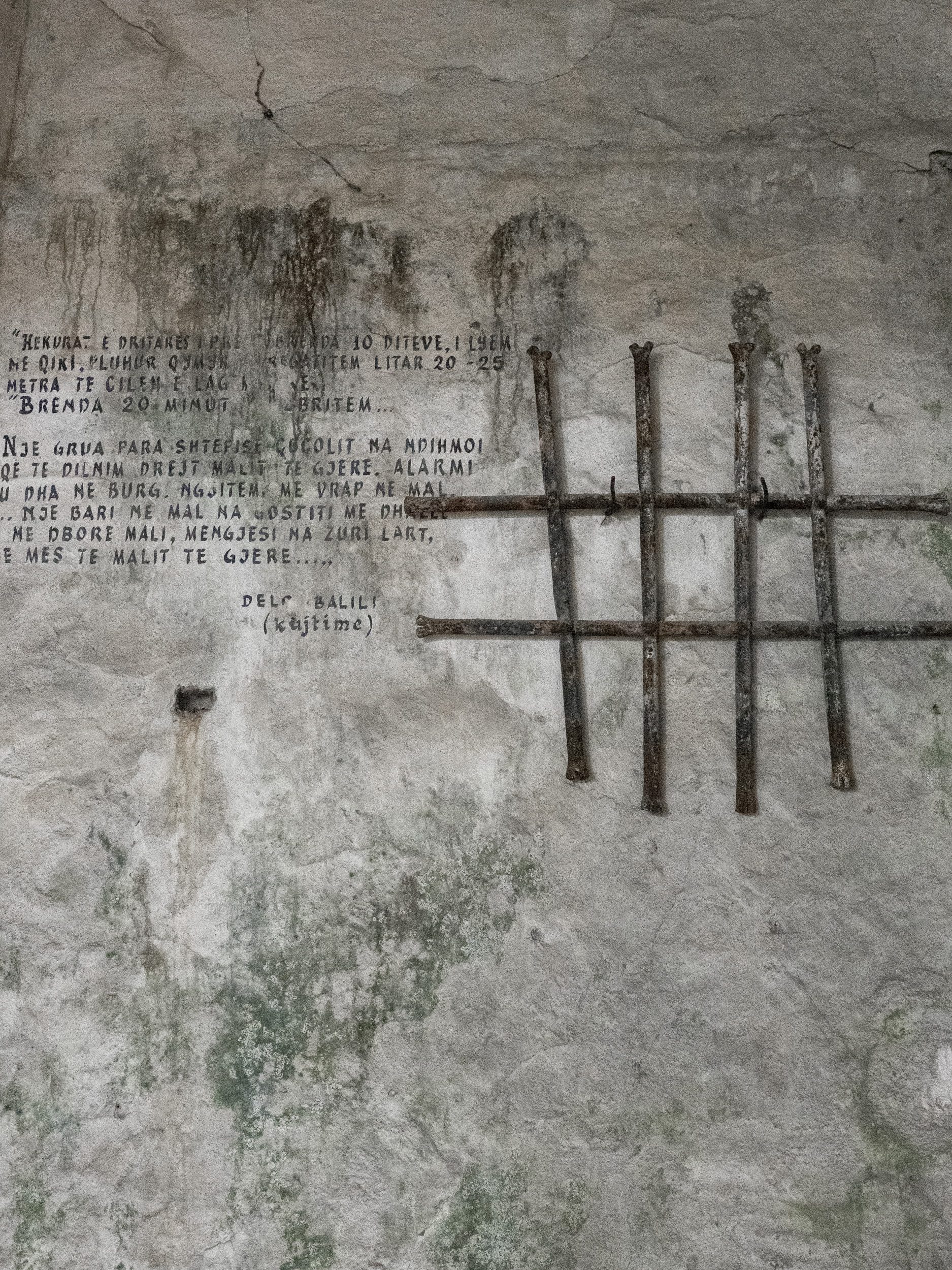

The castle of Gjirokaster hides many dark stories. From 1932, the administration of King Zog used it as a prison. Later, the communist party kept political inmates there. People called it the prison of seven windows. Some residents of Gjirokastra still remember the screams coming from the castle, and prisoners recall the ominous sound of guards hammering the bars in the windows to check if they are secure. They had to live in terrible conditions – in cold underground cells, with mice under their thin mattresses. They were frequently beaten and tortured, some to death. Some families of the inmates never found out what happened to their relatives who got arrested and never returned.

Lockheed T-33 Shooting Star

I left the dark rooms that witnessed the grim history and walked around the castle’s domain, bathed in the afternoon sun. As a whole Gjirokaster, it was full of surprises, like the American Lockheed T-33 Shooting Star plane that landed in Tirana in 1957.

How did it get here? There were two versions of the story, as with every story during the Cold War. The Albanian government claimed it was an American spy plane, and they tracked it down and downed it. The American version was that, because of the fog, the plane flying from France to Italy went off course and, running out of fuel, had to do an emergency landing in Albanian. It must have been quite an adventure for the pilot, one of the few foreigners who entered Albania during that time. He returned to the US a few weeks later, but the plane stayed in Albania.

Skenduli House

Skendulis used to be one of the wealthiest families in town, so rich even the dogs ate well, as Gjirokastrans used to say. My guide, Nesip Skenduli, was the 9th generation that lived in the house. In a mix of English, German, Italian, French and Russian, he showed me all corners of the Ottoman mansion.

-Secret communication – said Nesip with a playful smile, pushing this or another small door, one of 40 in the whole house.

The geography of the 18th-century house was fascinating. The rooms were connected with a web of corridors. One never knew what waited behind the next door. Without a guide, I wouldn’t be able to make my way back to the entrance.

I was astonished by the advanced solutions the architects of this house used.

-In Gjirokastra houses, even in the 18th century, the toilets were inside – said Nesip. – Outside – problem in winter and for the neighbours. Nasha doma 6 tualet, no problem per tschelavyek. Our house had six toilets. No problem per person – he laughed.

He proudly showed the four hammams (Turkish baths) and nine fireplaces.

-The more fireplaces in a house, the more prestige – Nesip explained.

There was even a refrigerator – a container with ice-cold water from the mountains, located below the ground floor. In case of a war, the family could hide in an underground bunker. The house had also 20 magic eyes – spying holes.

-To keep persona non grata away – said Nesip.

We walked and walked, following his warm voice. On the 3rd floor, we entered a bright room with beautiful wall paintings.

-Pommegranate, a symbol of wealth and fertility – explained the guide. We were in the bride’s room, where a young woman first prepared for her wedding day and after the ceremony enjoyed the moments with her new husband.

-Romantiko – Nesip pointed at the beautiful view from the wooden balcony. The panorama of the town and the mountains on the horizon were very romantic indeed.

Ali Pasha Bridge

As the heat released its sticky grip, I climbed the alley towards the Sopot mountain. An old Mercedes abruptly took off, leaving a smell of burned clutch behind. I passed by a few restaurants, and the staff of each of them tried to lure me for dinner.

-I might stop by on my way back. First, I go to the Ali Pasha Bridge – I politely declined each invitation.

The Ali Pasha bridge was not a bridge but a part of an aqueduct. The ruler requested to build it to supply the 200 families living inside the Gjirokaster castle with water, at least that’s what Kavi, a student and local history enthusiast told me.

Only half an hour after leaving the city centre, everything I saw was a rugged landscape. The stone construction stretched between two rocky slopes with impressive arches. It felt outlandish and remote. The air was still, and there was no noise until a flock of goats appeared on the other side of the valley. I stepped aside to make space for them on the trail.

The sun hid behind the mountain. I sat down on a rock and watched how the town, cast up in the valley, was being covered by shadow.

Nice descriptions, thank you! We are in the town right now…